The Shifting Politics of Cuba Policy

Source:

There was a time, not too long ago, when any mainstream politician running for statewide or national office in Florida had to rattle off fiery rhetoric against the Cuban government and declare unquestioning faith that the embargo on the island would one day force the Castros from power.

There was a time, not too long ago, when any mainstream politician running for statewide or national office in Florida had to rattle off fiery rhetoric against the Cuban government and declare unquestioning faith that the embargo on the island would one day force the Castros from power.

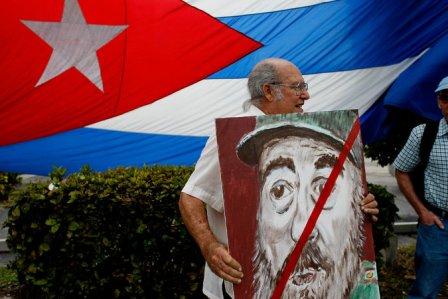

For generations, among Cuban-Americans, once a largely monolithic voting bloc, the embargo was a symbol of defiance in exile — more gospel than policy.

That has changed dramatically in recent years as younger members of the diaspora have staked out views that are increasingly in favor of deepening engagement with the island. Cuba still looms large in Florida politics, and to an extent nationally. But it is far from the clear-cut issue it once was.

That evolution has allowed a growing number of seasoned politicians to call the embargo a failure and argue that ending America’s enmity with Cuba represents the best chance of encouraging positive change on the island. Several prominent Cuban-American businessmen who were once strong supporters of the embargo have changed their stance and become proponents of engagement. The pro-embargo lobby raises a fraction of the money it once did. President Obama now receives more correspondence from lawmakers who favor expanded ties than from those who want to keep robust sanctions.

The shift has not been lost on the White House, where officials are deliberating over how much progress they might be able to make on President Obama’s longstanding interest in expanding ties with Cuba. Mr. Obama supported repealing the embargo when he was running for the United States Senate in 2004 but backtracked as a presidential candidate, saying in 2008 that the embargo gave Washington leverage over the Cuban government.

No bold move on Cuba policy would be risk-free. But the political backlash Mr. Obama would face by taking steps to normalize relations is likely to be manageable, even in the Cuban-American community, and well worth the opportunities there would be for expansion in trade, communications and relationships between Americans and ordinary Cubans.

Charlie Crist, the former governor of Florida who is in a tight race for his old job, recently said he was interested in traveling to Cuba, an idea he later scrapped, blaming a busy schedule. Mr. Crist, however, has emphatically said he has come to see the embargo as a relic that must be shelved. Hillary Rodham Clinton wrote in her memoirs, and repeated in a recent interview, that she now favors repealing the embargo, which she called a failure, because it has “propped up the Castros.”

In Florida, members of Congress have staked out positions on Cuba that once would have been considered political suicide. Representative Kathy Castor, a Democrat from Tampa, traveled to the island last year and made a strong appeal for an end to the sanctions, saying the United States was failing to capitalize on economic reforms underway on the island. She feels that far from hurting her politically, the stance has made her more popular among constituents, including Cuban-Americans, who want to play a role in the island’s future.

Continue reading the main story Continue reading the main story

Continue reading the main story

Even in Miami, where old-guard positions remain popular among older exiles, who are largely Republicans, there have been notable changes. In 2012, Joe Garcia became the first Cuban-American Democrat from Miami to be elected to the House. While he publicly supports the embargo, Mr. Garcia holds views significantly different from other South Florida members of Congress. For instance, he has called for clinical trials in the United States of a Cuban diabetes treatment that has shown great promise. He also favors easing travel restrictions to the island.

Still, ending the embargo, which requires congressional action, remains challenging because a small but passionate group of Cuban-American lawmakers is adamant about maintaining the status quo. The most vocal defenders of the embargo are Senator Robert Menendez, a Democrat from New Jersey; Senator Marco Rubio, a Republican from Florida; and Representative Ileana Ros-Lehtinen and Representative Mario Diaz-Balart, both Miami Republicans.

In April, during the height of the crisis set off by Russia’s invasion of Crimea, Mr. Menendez, the son of Cuban immigrants who moved to the United States in 1953, delivered a long, impassioned speech on the Senate floor, arguing that despite the myriad foreign policy crises in the world, Washington needed to focus on the abuses of “a Stalinist police state” 90 miles away. He displayed photos of dissidents and warned that expanded travel by Americans to Cuba was enabling a despotic state. White House officials fear that Mr. Menendez, as the chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, could hold up confirmation of federal nominees in retaliation for further moves to ease the embargo.

Mr. Menendez’s loathing of the Cuban government has only increased because he believes the island’s intelligence service sought to destroy his career by planting a fabricated story in the media suggesting that he had patronized underage prostitutes in the Dominican Republic.

White House officials are less concerned about pushback from Republicans, who are reflexive about criticizing the president on foreign policy. While a growing number of her congressional colleagues have traveled to Cuba, Ms. Ros-Lehtinen, who is among the most ardent supporters of the embargo, seems to be strikingly out of touch with what is happening on the island.

In a recent interview deploring a visit to Havana by Beyoncé and Jay-Z, Ms. Ros-Lehtinen expressed outrage that the celebrities had stayed in hotels where Cubans aren’t allowed to stay, even if they could afford it. As it happens, the Cuban government lifted that ban in 2008.

As the electorate has shifted on Cuba, some Cuban-American politicians have begun to call for a review of the policy that puts newly arrived Cubans on a fast track to citizenship, probably because new immigrants support closer ties with the island and grew up despising the embargo.

Politics aside, the issue remains deeply personal for the holdouts, Cuban-Americans of that generation say, because it continues to evoke raw feelings about ancestry, homeland and loss. Those sentiments, which have lasted for more than 50 years, cannot be ignored. But they should not continue to anchor American policy on a failed course that has strained Washington’s relationship with allies in the hemisphere, prevented robust trade with the island and offered the Cuban government a justification for its failures.