The First Congress, like another Revolution

Data:

Fonte:

Autor:

As if he were imitating a topographer, one of the many laboring on the Uruguay sugar mill’s water distribution system at that time, the man looked over the top of his hoe and found no sign of the end of the furrow he was working, which by around 11 am, had already drenched his shirt, pants and shoes in sweat.

"Gentlemen, I got the worst of all. This one should have been saved for Joaquín Bernal, the inventor of voluntary work in Sancti Spíritus," he said to his closest companions in the task.

But before the group's boisterous response to the speaker's wit died down, the unmistakable voice of Joaquín Bernal Camero himself was heard, at that time first secretary of the Provincial Party Committee, who was just three rows down, with a similar tangle of weeds to hoe. Hearing the conversation, he yelled, "Listen, friend, you finish yours, I'm going to get mine done and I assure you that it's not easy either."

Approached by Granma, in connection with the soon to be held Eighth Party Congress, the veteran Sancti Spíritus leader does not deny the veracity of the story, or of others told over and again around the region, attesting to his deep ties with the people, as mandated by Fidel who, he says, insisted that the Party always keep in mind, in the good times and the bad.

Joaquín, as he is still called in Sancti Spíritus three decades after the end of his term, did not need to strain his memory much to recall the period he describes as “tumultuous” and "of much learning," and in particular, his experience in connection with the First Congress of Cuban Communists (December 1975), an event during which he was recognized as an alternate member of the Central Committee, and given the difficult task of shaping a new province that had recently been established, including areas previously in three different territories.

"We went as delegates from one province - Las Villas - and then had to implement the approved policies in a different one, because the New Political Administrative Division began immediately (in mid-1976), and I became the first secretary of the CCP Provincial Committee in Sancti Spiritus," Bernal recalls.

By this time, this tobacco grower from Cabaiguán had already been well cured, self-taught and via political courses in the country and the former Soviet Union, and above all, on the street, listening to the people, conversing. He had been secretary of the CCP in the districts of Escambray, Sagua la Grande, Santa Clara and Sancti Spiritus, and organizer of the Party in the former province of Las Villas.

-So you were the relief pitcher?

Photo: Granma Archives

-To a large extent, yes. Milián (referring to the veteran communist fighter Arnaldo Milián Castro, then first secretary in Las Villas, promoted to Political Bureau member during the First Congress) would send me to places where there was a problem. I remember, when he put me in charge of the Santa Clara region, he kept me as organizer in the province, too, but when you’re young, everything is possible. I was in charge of the city during the day and the province by night, where, the fact is, I had a magnificent team."

Recalling the First Congress, which for Joaquín Bernal was "like another Revolution," he especially emphasizes the depth of discussions about the cadre policy and problems in the economy, the impressive Central Report presented by Fidel, and the atmosphere that prevailed during those days, as the epic in Angola was just beginning.

A meritorious central committee

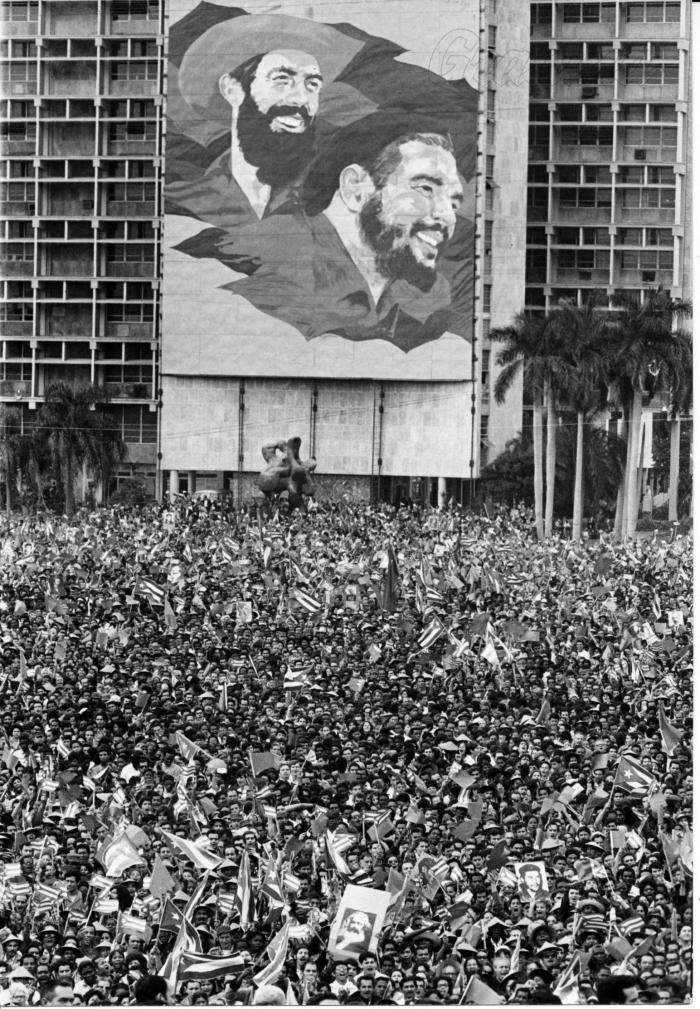

When Fabio Grobart, with his undisguisable Polish accent, presented "the founder, head and guide" of the Revolution as the first secretary of the Party Central Committee, he was recognizing not only Fidel's unquestionable credentials as the leader of the entire process that had radically changed the course of the country’s history, but also his role at the head of the political organization that he himself had built, with the patience of a goldsmith, a decade earlier.

Minutes later, Fidel himself would speak of the significance of the Congress for the nation and for the consolidation of the Party - its Political Bureau now strengthened with five valuable comrades: Blas Roca Calderío, "whose life is a monument to simplicity, modesty, work, identification with the workers’ cause; José Ramón Machado Ventura, "whose merits, character, prestige and authority are known to all;" Carlos Rafael Rodríguez, "whose capacity is proverbial, since even in the capitalist era, Carlos Rafael was spoken of with great respect;" Pedro Miret Prieto, "one of the first young university students to join the struggle with which this process began; and Arnaldo Milián Castro, for his "brilliant work leading the province of Las Villas."

Heir to the same unifying tradition with which the Party was constituted in 1965, the new Central Committee, like society itself, was painted in black and white, included women, and was enriched by previously anonymous individuals like the internationalist fighter in Guinea Bissau, Pedro Rodríguez Peralta, at that time in a Portuguese colonial prison; cane cutter Reinaldo Castro, who harvested a million sheaths by himself in one season; Pilar Fernández, a modest factory worker; the scientist Zoilo Marinello; and poet Nicolás Guillén.

Fidel explained to the delegates and 86 international delegations of guests gathered in the Karl Marx Theater that, although "nepotism cannot and will never exist” in the Party or the Revolution, “sometimes two cadres get together," before announcing what he considered a privilege, a Party second secretary who "in addition to being an extraordinary revolutionary cadre, is also a brother."

The family relationship had in fact served the older brother well, allowing him to enlist Raúl in the revolutionary process and invite him to join the Moncada assault, the Comandante en jefe stated, during the closing ceremony, adding "That was the beginning. And then came prison, and exile, the Granma expedition, the difficult moments, and the Second Front, and the work done during all these years," he said, recalling Raul's path.

Congress documents worth rereading

More than a compendium of figures and ideas, the Central Report to the First Party Congress was a portrait of the economic, political and social life of the country, after 16 years of Revolution, "a decisive document," according to Joaquin Bernal, one of the 3,116 delegates participating in the gathering, which outlined the accomplishments of that stage in the construction of Cuban socialism, as well as the mistakes committed during the period.

"The discussions in commissions were tough,” recalls Dagoberto Pérez Pérez, delegate from the Escambray region, in the former province of Las Villas. We advocated the thesis that it was impossible to study while working. I remember that Julio Camacho Aguilera conducted the debate masterfully, and in the end, convinced us otherwise."

But it was not only the Central Report that was "cooked up," during the Congress. The working sessions held between December 17 and 22, 1975, also produced the Party’s Programmatic Platform; the Draft Constitution of the Republic of Cuba, eventually approved in a popular referendum on February 24, 1976; a new Political Administrative Division, which was implemented in 1976 to put an end to the old colonial territorial structure; as well as the Theses and Resolutions on various areas of national life.

Although more than twenty of the latter were approved, it is obvious that some of these documents are limited to the times, others to very specific issues, or the internal life of the organization, but, most have a universal scope and an undeniable relevance in the light of our current reality.

Such is the case of the Theses and Resolutions’ references to the full exercise of the equality of women; the Constitution and the Law of Constitutional Transition; the agrarian question and relations with the peasantry; artistic and literary culture; the Political Administrative Division; the education of children and youth; the ideological struggle; the Party’s Programmatic Platform; the policy of training, selection, placement, promotion and development of cadres; policies regarding religion, the church and believers; international policy; People's Power bodies; the mass media, directives for economic and social development in the five-year period 1976-1980; national scientific and educational policies.

Now that two bills are being presented in the U.S. state of Florida to educate about "the horrors of communism," requiring mastery of the subject to graduate from high school, while in Spain, Madrid's President Isabel Diaz Ayuso has launched a "communism or freedom" campaign, it is worth recalling that the Theses and Resolutions, approved 45 years ago by Cuban communists, eloquently embraced the Leninist maxim that "socialism is impossible without democracy."

The Theses note, "Anti-communism is directed not only against Marxism-Leninism, but against all democratic and progressive thought, against all ideas that could create obstacles to the objectives of reactionary classes;" a truth that, at least on the American continent, has been made clear in Cuba, as well as Argentina, Venezuela and Nicaragua, Honduras, Ecuador, Brazil, Bolivia, and every corner of the planet where anti-hegemonic ideas have appeared.

The Theses and Resolutions on the ideological struggle explicitly identify the enemies of the Revolution who distort and falsify the political experience of our insurrectional struggle, and those who attempt to demonstrate that the Cuban Revolution is an "unrepeatable exceptionality", or that our experience contradicts the Marxist-Leninist thesis on the necessity of a party in a socialist revolution, and emphasize the need to combat such falsehoods with the force of historically proven truth. Cuba was not and is not an exception, "but rather the confirmation of the extraordinary force of the ideas of Marx, Engels and Lenin."

Another example of the continuing relevance of the documents approved at the 1st Congress is worth mentioning: At a time when our culture and Cuban creators are being harassed in an unprecedented manner by a well-paid and organized media machine, the Theses and Resolutions on artistic and literary culture note, "Socialist society requires art which, through aesthetic enjoyment, contributes to the education of the people." This does not imply limiting the role of art to a merely didactic one, but does reject vulgarity and mediocrity in all of their manifestations.

In the relatively distant year of 1975, the Party Congress advocated what the Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba and the Saiz Brothers Association repeatedly demand today: Artistic and literary criticism that recognizes quality, and at the same time is able to point out the flaws of the work in question.

Just days after the closing of the First Congress, the new Constitution of the Republic of Cuba was submitted to popular referendum; regional authorities began functioning on the basis of new geographical limits established by the approved Political Administrative Division; and that by the end of 1976, local Popular Power bodies were taking shape – events that constitute just three examples showing that the decisions made at the event were not to be shelved.

A philosophy for all times

The Eighth Party Congress has been described as the Congress of continuity, not only because of the sustained process of a generational change in leadership, but also - and this is no less important - because, while needed transformations and updates continue, the course of the Revolution remains the same.

As stated in the new Constitution approved by the National Assembly and endorsed by the vote of the overwhelming majority of Cubans in 2019, the Communist Party of Cuba maintains its status as "the highest leading political force of society and the state;" socialist property remains fundamental, although others are recognized; foreign policy is as principled and independent as it was 45 years ago; social achievements - health, education, employment, social security, etc. - are a priority for the Party itself, the government and the state.

The elimination of racial discrimination and the struggle for women's equality have been two of the Revolution’s critical projects since day one, updated as the times have demanded, and sustained on the basis of a scientific perspective, also encouraged and developed by the Cuban state, despite insidious campaigns.

This is how Dagoberto Perez Perez, a veteran Party leader and small farmer in Jiquima de Pelaez, in the municipality of Cabaiguan, feels as he recalls standing amazed, in front of those huge curtains of the Karl Marx Theater, which moved back and forth like palm fronds in the wind, one fine day in December 1975.

"When I see all these tours Díaz-Canel makes, and all the problems he is dealing with, day by day, it is as if I were seeing the same Fidel of those times," he confesses, sitting in his house on Céspedes Street, in the city of Sancti Spíritus, where he preserves his badge, faded by time, from the First Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba.

Born in 1935, Dagoberto studied auto mechanics by correspondence, participated in strikes and sold July 26th movement bonds, until, suddenly, he found himself in the middle of the revolutionary hurricane, which lead him to the Party’s work, serving as first secretary of locals in the municipalities of Caracusey and Condado, in Trinidad, and organizer, first in the Escambray region, and then in the new province of Sancti Spíritus.

Before taking on this responsibility, René Anillo Capote summoned him and another group of young people to the headquarters of the CCP in Santa Clara, former capital of Las Villas, where he surprised them with news that none of them understood at that time, June of 1963, saying "You are going to build the Party in the Escambray."

Not much time passed after that meeting, before they were climbing into a jeep on their way to Manicaragua, and coming face to face with the leader of the struggle against counterrevolutionary bands, Eugenio Urdandibel, who was already organizing his people on the ground.

-Who here knows how to drive," he asked.

-Well, knowing, what is called knowing, I know, just that I don't have a license," Dagoberto replied.

-You don’t need one," Urdandibel barked, and then fired another question.

-Do you have a backpack?

-Yes, I do.

-Well, that's all there is to it, if you know how to drive and you have a backpack, you're on. You go to the battalions, and be careful, because the Escambray is at war.